Frank Lloyd Wright Architecture Tour in Oak Park (Self Guided), Chicago

Oak Park, located in Cook County, Illinois, just outside Chicago, made history in 1889 when Frank Lloyd Wright, one of America's most renowned architects, and his wife settled there, leaving a profound impact on the area's appearance. This village boasts the highest concentration of Wright-crafted buildings in the world - over a dozen! - making it a pivotal destination for enthusiasts to admire his work.

Starting with the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, where Wright kick-started his career, this tour allows visitors to witness where the architect experimented with design concepts that later defined his Prairie School style. This landmark serves as the gateway to the rest of Wright's creations in Oak Park.

As you progress through the neighborhood, each house on the tour stands out with its distinct features yet shares the unified aesthetic that Wright is famous for. The Walter Gale House, Thomas H Gale House, and Robert P Parker House are prime examples of Wright’s early explorations into the Prairie style, characterized by overhanging eaves and horizontal lines that mimic the natural prairie landscape.

The William H Copeland House, Nathan G Moore House, and Arthur Heurtley House further showcase Wright’s evolution in residential design, offering a deeper understanding of his architectural philosophy. The Edward R Hills House and the remodel of the Laura Gale House reflect Wright’s maturation in integrating his designs with their environments.

The tour also highlights Wright's ingenuity through the Peter A Beachy House, Frank W Thomas House, and particularly the Unity Temple. This latter building, a massive structure for the Unitarian Universalist church, emphasizes Wright’s mastery of concrete and his innovative use of light and space, marking a significant evolution in his architectural journey.

Additional stops like the Oscar Balch House and the Harry S Adams House round out the tour, each contributing to the narrative of Wright’s pioneering work and its impact on American architecture.

To truly experience the genius of Frank Lloyd Wright, visiting Oak Park is a must. Whether you're an architecture buff or simply someone who appreciates great design, the Oak Park tour offers an enriching, educational experience. Take this self-guided walk through the living history of architecture that Wright left behind.

Starting with the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, where Wright kick-started his career, this tour allows visitors to witness where the architect experimented with design concepts that later defined his Prairie School style. This landmark serves as the gateway to the rest of Wright's creations in Oak Park.

As you progress through the neighborhood, each house on the tour stands out with its distinct features yet shares the unified aesthetic that Wright is famous for. The Walter Gale House, Thomas H Gale House, and Robert P Parker House are prime examples of Wright’s early explorations into the Prairie style, characterized by overhanging eaves and horizontal lines that mimic the natural prairie landscape.

The William H Copeland House, Nathan G Moore House, and Arthur Heurtley House further showcase Wright’s evolution in residential design, offering a deeper understanding of his architectural philosophy. The Edward R Hills House and the remodel of the Laura Gale House reflect Wright’s maturation in integrating his designs with their environments.

The tour also highlights Wright's ingenuity through the Peter A Beachy House, Frank W Thomas House, and particularly the Unity Temple. This latter building, a massive structure for the Unitarian Universalist church, emphasizes Wright’s mastery of concrete and his innovative use of light and space, marking a significant evolution in his architectural journey.

Additional stops like the Oscar Balch House and the Harry S Adams House round out the tour, each contributing to the narrative of Wright’s pioneering work and its impact on American architecture.

To truly experience the genius of Frank Lloyd Wright, visiting Oak Park is a must. Whether you're an architecture buff or simply someone who appreciates great design, the Oak Park tour offers an enriching, educational experience. Take this self-guided walk through the living history of architecture that Wright left behind.

How it works: Download the app "GPSmyCity: Walks in 1K+ Cities" from Apple App Store or Google Play Store to your mobile phone or tablet. The app turns your mobile device into a personal tour guide and its built-in GPS navigation functions guide you from one tour stop to next. The app works offline, so no data plan is needed when traveling abroad.

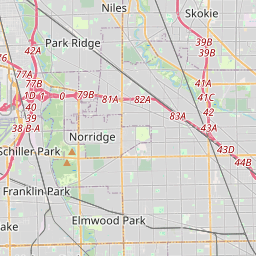

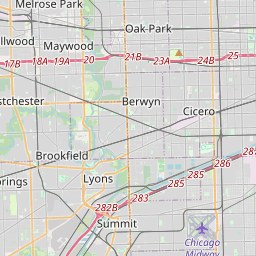

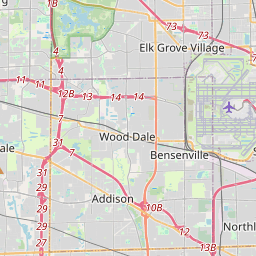

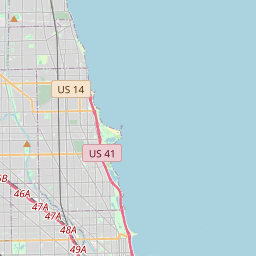

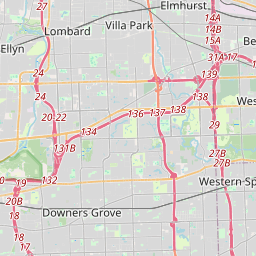

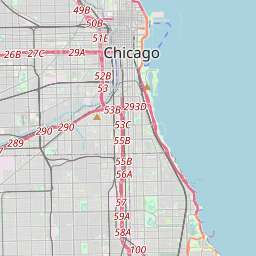

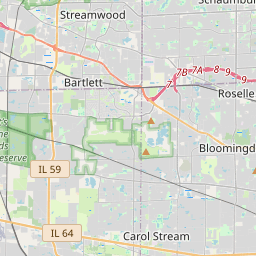

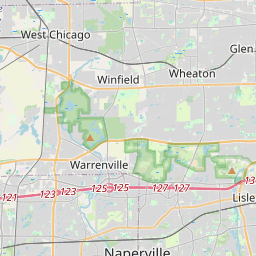

Frank Lloyd Wright Architecture Tour in Oak Park Map

Guide Name: Frank Lloyd Wright Architecture Tour in Oak Park

Guide Location: USA » Chicago (See other walking tours in Chicago)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 14

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.2 Km or 2 Miles

Author: Daniel

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

Guide Location: USA » Chicago (See other walking tours in Chicago)

Guide Type: Self-guided Walking Tour (Sightseeing)

# of Attractions: 14

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.2 Km or 2 Miles

Author: Daniel

Sight(s) Featured in This Guide:

- Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio

- Walter Gale House

- Thomas H. Gale House

- Robert P. Parker House

- William H. Copeland House

- Nathan G. Moore House

- Arthur Heurtley House

- Edward R. Hills House

- Laura Gale House

- Peter A. Beachy House

- Frank W. Thomas House

- Unity Temple

- Oscar Balch House

- Harry S. Adams House

1) Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio

The Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio serves as a monumental piece in the architectural legacy of one of the 20th century's most influential architects. Initially constructed in 1889, this residence and workspace were extensively modified by Wright himself over the years, reflecting his evolving design philosophy. The building, which is furnished with original Wright-designed furniture and textiles, has been meticulously restored by the Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust to mirror its 1909 appearance—the last year Wright resided there with his family.

The structure itself integrates elements of the Shingle style, popular among the affluent East Coast society and favored by Wright's one-time employer, Joseph Lyman Silsbee. One of the most remarkable spaces within the home is the 1895 playroom designed for his children, which showcases an early use of architectural elements that Wright would refine throughout his career. The playroom features a high, barrel-vaulted ceiling supported by walls of Roman brick, with a central skylight adorned with wood grilles depicting stylized blossoms and seedpods, providing soft, natural light.

In 1898, the addition of a new Studio wing marked a significant expansion of Wright’s professional capabilities. Financed by a commission from the Luxfer Prism Company, the Studio was strategically positioned facing Chicago Avenue and connected to his residence via a corridor. This new wing included a reception hall that served dual purposes as a waiting area for clients and a space for Wright to discuss plans with contractors. The heart of this addition was the dramatic two-story drafting room, which became the creative epicenter of Wright’s architectural practice. Here, surrounded by expansive drafting tables and abundant natural light, Wright and his associates crafted designs that would revolutionize American architecture.

Today, the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio is not only a National Historic Landmark but also a key component of the Frank Lloyd Wright–Prairie School of Architecture Historic District. Visitors to the site can experience the intimate spaces where Wright conceived some of his most groundbreaking architectural ideas, making it a pilgrimage site for those captivated by architectural history and Wright’s enduring influence.

The structure itself integrates elements of the Shingle style, popular among the affluent East Coast society and favored by Wright's one-time employer, Joseph Lyman Silsbee. One of the most remarkable spaces within the home is the 1895 playroom designed for his children, which showcases an early use of architectural elements that Wright would refine throughout his career. The playroom features a high, barrel-vaulted ceiling supported by walls of Roman brick, with a central skylight adorned with wood grilles depicting stylized blossoms and seedpods, providing soft, natural light.

In 1898, the addition of a new Studio wing marked a significant expansion of Wright’s professional capabilities. Financed by a commission from the Luxfer Prism Company, the Studio was strategically positioned facing Chicago Avenue and connected to his residence via a corridor. This new wing included a reception hall that served dual purposes as a waiting area for clients and a space for Wright to discuss plans with contractors. The heart of this addition was the dramatic two-story drafting room, which became the creative epicenter of Wright’s architectural practice. Here, surrounded by expansive drafting tables and abundant natural light, Wright and his associates crafted designs that would revolutionize American architecture.

Today, the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio is not only a National Historic Landmark but also a key component of the Frank Lloyd Wright–Prairie School of Architecture Historic District. Visitors to the site can experience the intimate spaces where Wright conceived some of his most groundbreaking architectural ideas, making it a pilgrimage site for those captivated by architectural history and Wright’s enduring influence.

2) Walter Gale House

The Walter Gale House represents a significant milestone in the career of Frank Lloyd Wright. Constructed shortly after his acrimonious departure from the architectural firm Adler and Sullivan in 1893, this house marks the beginning of Wright's independent architectural practice. Commissioned by Walter H. Gale, a member of a prominent local family, the house stands as a bold declaration of Wright's design philosophy and his readiness to innovate. Notably, the Walter Gale House was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1973, underscoring its importance in the annals of American architecture.

Architecturally, the house is distinguished by its striking façade, which features a large circular turret, a defining element of the structure. This rounded turret on the right of the house is artistically balanced by a narrow, angular dormer that extends two stories, from the second floor to the attic on the left side. This interplay of rounded and angular forms is a hallmark of Wright’s early experimentation with geometric shapes and volumes, foreshadowing the mature style that would later become his signature.

Inside, the second floor primary bedroom showcases a continuous band of curved windows outfitted with diamond-paned leaded glass, enveloping the room in a panoramic embrace of natural light. This design element closely mirrors the aesthetic Wright employed in the semi-circular dining room bay of the 1893 William Winslow House, indicating a cohesive development in his architectural vocabulary. These uninterrupted groupings of windows not only enhance the structural dynamism of the house but also reflect Wright's growing interest in integrating the interior with the exterior environment.

Architecturally, the house is distinguished by its striking façade, which features a large circular turret, a defining element of the structure. This rounded turret on the right of the house is artistically balanced by a narrow, angular dormer that extends two stories, from the second floor to the attic on the left side. This interplay of rounded and angular forms is a hallmark of Wright’s early experimentation with geometric shapes and volumes, foreshadowing the mature style that would later become his signature.

Inside, the second floor primary bedroom showcases a continuous band of curved windows outfitted with diamond-paned leaded glass, enveloping the room in a panoramic embrace of natural light. This design element closely mirrors the aesthetic Wright employed in the semi-circular dining room bay of the 1893 William Winslow House, indicating a cohesive development in his architectural vocabulary. These uninterrupted groupings of windows not only enhance the structural dynamism of the house but also reflect Wright's growing interest in integrating the interior with the exterior environment.

3) Thomas H. Gale House

The Thomas H. Gale House stands as a pivotal piece in the architectural evolution of Frank Lloyd Wright. This house, along with two others on Chicago Avenue, forms part of Wright’s early forays into independent architectural design, famously known as his "Bootleg Houses." Designed clandestinely in 1891-1892 while Wright was still employed at the architectural firm Adler and Sullivan, these houses were a bold step for Wright, showcasing his burgeoning design ethos even as he risked his career. The discovery of these secret commissions by Louis Sullivan led to Wright's departure from the firm and the start of his illustrious solo career in 1893.

The Thomas H. Gale House is particularly notable for its architectural style, which offers clear transitional elements that would eventually culminate in Wright’s development of the Prairie style. The structure features a high-pitched roof and octagonal dormers and bay, creating a complex interplay of shapes reminiscent of the Queen Anne style, popularized by British architect Richard Norman Shaw. However, Wright's design eschews the ornate decorative flourishes typical of Queen Anne, opting instead for a more restrained sophistication that hints at the elemental simplicity he would later champion in his Prairie homes.

Despite its conventional form, the Gale House embodies Wright’s innovative spirit and his early experiments with integrating form and function. This approach is evident in how Wright balances the traditional with the modern, stripping away superfluous decoration to focus on structural integrity and a unified aesthetic.

Designated an Oak Park Landmark in 2002, the Thomas H. Gale House continues to be celebrated not just as a piece of architectural history but as a testament to Wright's early vision and his daring to innovate beyond the norms of his time.

The Thomas H. Gale House is particularly notable for its architectural style, which offers clear transitional elements that would eventually culminate in Wright’s development of the Prairie style. The structure features a high-pitched roof and octagonal dormers and bay, creating a complex interplay of shapes reminiscent of the Queen Anne style, popularized by British architect Richard Norman Shaw. However, Wright's design eschews the ornate decorative flourishes typical of Queen Anne, opting instead for a more restrained sophistication that hints at the elemental simplicity he would later champion in his Prairie homes.

Despite its conventional form, the Gale House embodies Wright’s innovative spirit and his early experiments with integrating form and function. This approach is evident in how Wright balances the traditional with the modern, stripping away superfluous decoration to focus on structural integrity and a unified aesthetic.

Designated an Oak Park Landmark in 2002, the Thomas H. Gale House continues to be celebrated not just as a piece of architectural history but as a testament to Wright's early vision and his daring to innovate beyond the norms of his time.

4) Robert P. Parker House

The Robert P. Parker House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1892, was among several homes Wright designed while he was still employed at the architectural firm Adler & Sullivan. The Parker House is recognized as a contributing property to a U.S. federally Registered Historic District, underscoring its importance in the architectural history of Chicago.

Architecturally, the Robert P. Parker House shares similarities with the Thomas H. Gale House, particularly in its plan and design which emphasize bold, geometric forms—a hallmark of Wright’s early style. One of the house's most distinctive features is an octagonal turret adjacent to the entrance, which itself is sheltered by a shallow overhanging eave. This design not only enhances the house's exterior aesthetic but also serves a functional purpose by protecting the entrance area. Upon entering the house, one finds an octagonal reception room, which leads to the library and dining room on the left, showcasing Wright's preference for both symmetry and fluidity in living spaces.

The interior of the house continues to reflect Wright's early explorations in space utilization and design harmony. The second floor is efficiently laid out with four bedrooms and a bathroom, offering a practical yet aesthetically pleasing living space. Originally commissioned by real estate agents Walter and Thomas Gale, the house was subsequently sold to Robert P. Parker later that same year, after whom it is now named.

Architecturally, the Robert P. Parker House shares similarities with the Thomas H. Gale House, particularly in its plan and design which emphasize bold, geometric forms—a hallmark of Wright’s early style. One of the house's most distinctive features is an octagonal turret adjacent to the entrance, which itself is sheltered by a shallow overhanging eave. This design not only enhances the house's exterior aesthetic but also serves a functional purpose by protecting the entrance area. Upon entering the house, one finds an octagonal reception room, which leads to the library and dining room on the left, showcasing Wright's preference for both symmetry and fluidity in living spaces.

The interior of the house continues to reflect Wright's early explorations in space utilization and design harmony. The second floor is efficiently laid out with four bedrooms and a bathroom, offering a practical yet aesthetically pleasing living space. Originally commissioned by real estate agents Walter and Thomas Gale, the house was subsequently sold to Robert P. Parker later that same year, after whom it is now named.

5) William H. Copeland House

The William H. Copeland House, originally constructed in 1875 in the Italianate style, underwent significant modifications under the guidance of Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909. The house, owned by William Copeland, a physician and manufacturer of patent medicines, reflects Wright's transformative architectural approach during the remodeling. Wright's revisions were designed to open the house to more natural light and give the structure and its accompanying garage a more unified and horizontal appearance, a departure from the vertically oriented Italianate style.

Wright's renovations were comprehensive and focused heavily on simplifying the existing structure. He removed ornamental elements from the façade, which were typical of the Italianate style, and enlarged the eaves to emphasize the horizontal lines that were becoming a hallmark of his developing Prairie style. Internally, Wright introduced dark wood stringcourses along the walls of the tall-ceilinged rooms. These stringcourses ran uninterrupted around the rooms, lowering the apparent ceiling height and enhancing the sense of spaciousness and continuity from one room to the next. This design strategy was part of Wright’s broader aim to create free-flowing interior spaces that were both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

Wright's attention to detail extended to the furniture and fixtures within the Copeland House. He designed specific pieces for the home, including a built-in sideboard for the dining room and a renovated fireplace in the reception room, ensuring that each element conformed to the overall aesthetic of the remodel. The detached garage also received Wright's touch; he replaced its steeply pitched roof with a lower, hipped roof that aligned with his Prairie style designs, added a ground-floor shop, and converted the second story into an apartment, complete with a hall, living room, bedroom, and closet.

The connections between the Copeland family and other notable figures in Wright's circle underscore the intertwined relationships of the era. Copeland’s daughter, Frances, married Walter Pratt Beachy, whose family also resided in a Wright-designed home and who later went on to co-found the Red Square Company with John Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, and develop Lincoln Logs.

Wright's renovations were comprehensive and focused heavily on simplifying the existing structure. He removed ornamental elements from the façade, which were typical of the Italianate style, and enlarged the eaves to emphasize the horizontal lines that were becoming a hallmark of his developing Prairie style. Internally, Wright introduced dark wood stringcourses along the walls of the tall-ceilinged rooms. These stringcourses ran uninterrupted around the rooms, lowering the apparent ceiling height and enhancing the sense of spaciousness and continuity from one room to the next. This design strategy was part of Wright’s broader aim to create free-flowing interior spaces that were both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

Wright's attention to detail extended to the furniture and fixtures within the Copeland House. He designed specific pieces for the home, including a built-in sideboard for the dining room and a renovated fireplace in the reception room, ensuring that each element conformed to the overall aesthetic of the remodel. The detached garage also received Wright's touch; he replaced its steeply pitched roof with a lower, hipped roof that aligned with his Prairie style designs, added a ground-floor shop, and converted the second story into an apartment, complete with a hall, living room, bedroom, and closet.

The connections between the Copeland family and other notable figures in Wright's circle underscore the intertwined relationships of the era. Copeland’s daughter, Frances, married Walter Pratt Beachy, whose family also resided in a Wright-designed home and who later went on to co-found the Red Square Company with John Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, and develop Lincoln Logs.

6) Nathan G. Moore House

The Nathan G. Moore House, also known as the Moore-Dugal Residence, is a striking example of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural versatility and his ability to cater to the specific tastes of his clients while still imprinting his unique style. Located just a block from Wright's own home and studio in Oak Park, the house was originally constructed to meet the preferences of attorney Nathan Moore, who favored traditional English architectural aesthetics. Completed in the Tudor style, the house features half-timbered upper stories and steeply pitched roofs that evoke a medieval European character, a stark contrast to the Prairie style that Wright was concurrently developing and popularizing.

Despite its adherence to a more conventional style, Wright introduced elements that broke from strict traditionalism. Notably, he added a uniquely designed porch at the front of the house, providing a hint of his innovative spirit amidst the traditional facade. This blend of the conventional with the innovative is a testament to Wright's architectural genius and his ability to balance client desires with his own design principles.

The house underwent significant changes following a fire in 1922 that destroyed the upper stories. Wright was given the opportunity to redesign these levels, and the modifications he made in 1923 marked a departure from the original Tudor revival style. The rebuilt structure incorporated elements typical of Wright's works from the late 1910s and early 1920s, including ornate detailing influenced by Sullivanesque, Mayan, and other exotic stylistic sources. While these additions stayed evocative of Tudor architecture, they also reflected Wright’s distinctive approach to blending different architectural influences. Today, the Nathan G. Moore House remains largely as Wright redesigned it in 1923 and continues to serve as a private residence.

Despite its adherence to a more conventional style, Wright introduced elements that broke from strict traditionalism. Notably, he added a uniquely designed porch at the front of the house, providing a hint of his innovative spirit amidst the traditional facade. This blend of the conventional with the innovative is a testament to Wright's architectural genius and his ability to balance client desires with his own design principles.

The house underwent significant changes following a fire in 1922 that destroyed the upper stories. Wright was given the opportunity to redesign these levels, and the modifications he made in 1923 marked a departure from the original Tudor revival style. The rebuilt structure incorporated elements typical of Wright's works from the late 1910s and early 1920s, including ornate detailing influenced by Sullivanesque, Mayan, and other exotic stylistic sources. While these additions stayed evocative of Tudor architecture, they also reflected Wright’s distinctive approach to blending different architectural influences. Today, the Nathan G. Moore House remains largely as Wright redesigned it in 1923 and continues to serve as a private residence.

7) Arthur Heurtley House

The Arthur Heurtley House stands as a seminal piece in the development of Frank Lloyd Wright's distinctive Prairie style, a design philosophy that sought to create buildings that were harmonious with the flat, expansive U.S. Midwest landscape. Commissioned in 1902 by Arthur Heurtley, one of Wright’s wealthier clients, the house exemplifies several innovative features that would later become hallmarks of Wright's Prairie-style homes. Among its most striking features is the absence of a traditional basement or attic, a decision that underscored the house's emphasis on horizontal lines and a streamlined, modern aesthetic that was revolutionary at the time.

The exterior of the Heurtley House is particularly notable for its sophisticated use of brickwork. Wright chose to dye the vertical mortar to match the bricks, while leaving the horizontal mortar in its natural color, effectively highlighting the building's elongated, earth-hugging lines. This horizontal emphasis is further enhanced by a continuous ribbon of art glass windows that run beneath the substantial overhang of the house’s hipped roof, allowing natural light to filter into the home while also providing a sense of privacy and seclusion.

Inside, the Heurtley House features an interior layout that was radical for its time. Wright chose to reverse the conventional floor plan, placing the main living and dining areas on the second floor rather than the ground level. This arrangement took full advantage of the surrounding views and emphasized the separation of public and private spaces within the home. The house’s interior, with its open spaces and flow between rooms, reflects Wright’s vision of a living environment that was both functional and aesthetically pleasing, free from the constraints of traditional residential design.

Over the years, the Heurtley House has been well-preserved and was subject to a museum-grade restoration in 1997 by then-owners Ed and Diana Baehren. Despite its significance in the pantheon of American architecture, the house remains privately owned and is not open to the public. This seclusion adds to the mystique of the property, preserving its integrity as a residential space while also serving as a testament to Wright’s enduring influence on modern architectural design.

The exterior of the Heurtley House is particularly notable for its sophisticated use of brickwork. Wright chose to dye the vertical mortar to match the bricks, while leaving the horizontal mortar in its natural color, effectively highlighting the building's elongated, earth-hugging lines. This horizontal emphasis is further enhanced by a continuous ribbon of art glass windows that run beneath the substantial overhang of the house’s hipped roof, allowing natural light to filter into the home while also providing a sense of privacy and seclusion.

Inside, the Heurtley House features an interior layout that was radical for its time. Wright chose to reverse the conventional floor plan, placing the main living and dining areas on the second floor rather than the ground level. This arrangement took full advantage of the surrounding views and emphasized the separation of public and private spaces within the home. The house’s interior, with its open spaces and flow between rooms, reflects Wright’s vision of a living environment that was both functional and aesthetically pleasing, free from the constraints of traditional residential design.

Over the years, the Heurtley House has been well-preserved and was subject to a museum-grade restoration in 1997 by then-owners Ed and Diana Baehren. Despite its significance in the pantheon of American architecture, the house remains privately owned and is not open to the public. This seclusion adds to the mystique of the property, preserving its integrity as a residential space while also serving as a testament to Wright’s enduring influence on modern architectural design.

8) Edward R. Hills House

The Edward R. Hills House, also known as the Hills–DeCaro House, embodies a fascinating blend of architectural styles that reflect different periods of Frank Lloyd Wright's illustrious career. Initially built in the late 19th century in the Stick style, the structure was notably transformed by Wright in a 1906 remodel into his signature Prairie style. This modification included the addition of features typical of Wright’s design philosophy during that period, such as horizontal lines, flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves, and windows grouped in horizontal bands. The house is now listed as a contributing property to a federal historic district on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and is recognized locally as an Oak Park Landmark.

Over the years, the Hills–DeCaro House has undergone significant changes, including several remodels that have added layers of complexity to its architectural narrative. Wright’s 1906 transformation was particularly dramatic, involving moving the original structure and completely rebuilding it. Further alterations between 1912 and 1965 gradually obscured some of Wright’s intended designs. A major turning point came in 1976 when a fire during a restoration project significantly damaged the structure, necessitating immediate reconstruction and partial restoration, which was further continued by subsequent homeowners.

Today, the Edward R. Hills House stands as a testament to the resilience and enduring appeal of Wright’s architectural vision, despite the multiple hands it has passed through and the changes it has undergone. The house not only showcases elements of Wright’s Prairie style but also retains traces of the experimental approaches he employed in the 1890s. Its exterior, finished in stucco with dark wood trim, and the thoughtful addition of two verandas on the first floor during the 1906 remodel, highlight Wright’s unique ability to blend functionality with aesthetic elegance.

Over the years, the Hills–DeCaro House has undergone significant changes, including several remodels that have added layers of complexity to its architectural narrative. Wright’s 1906 transformation was particularly dramatic, involving moving the original structure and completely rebuilding it. Further alterations between 1912 and 1965 gradually obscured some of Wright’s intended designs. A major turning point came in 1976 when a fire during a restoration project significantly damaged the structure, necessitating immediate reconstruction and partial restoration, which was further continued by subsequent homeowners.

Today, the Edward R. Hills House stands as a testament to the resilience and enduring appeal of Wright’s architectural vision, despite the multiple hands it has passed through and the changes it has undergone. The house not only showcases elements of Wright’s Prairie style but also retains traces of the experimental approaches he employed in the 1890s. Its exterior, finished in stucco with dark wood trim, and the thoughtful addition of two verandas on the first floor during the 1906 remodel, highlight Wright’s unique ability to blend functionality with aesthetic elegance.

9) Laura Gale House

The Laura R. Gale House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909, is a notable example of the architect's pioneering work during his most productive Prairie style period. Located on a quaint, winding street in Oak Park, the house was commissioned by Laura R. Gale, the widow of realtor Thomas Gale, marking another collaboration between Wright and the Gale family who had previously engaged him to design properties on Chicago Avenue—part of Wright's "bootleg" ventures. The house stands as a testament to Wright's evolving architectural philosophy, blending simplicity with functional elegance, and is constructed from stucco and wood, fitting seamlessly into its narrow lot.

The architectural design of the Gale House is modest yet impactful, with its innovative use of space and structure. The entrance, subtly hidden behind a tall pier, opens into a hall dominated by a massive Roman brick fireplace, which artfully separates the hall from the living room. Built-in shelving and slightly elevated dining room floors, along with dramatically cantilevered balconies, are distinctive features that showcase Wright's skill in integrating interior spaces with external forms. The house's second story, which includes four bedrooms and a maid’s room, is enhanced by a cantilevered balcony that joins the north-facing bedrooms, offering a unique architectural element that presages some of Wright's later, more famous works.

The design significance of the Laura Gale House extends beyond its physical boundaries. Wright himself regarded this residence as the “progenitor of Fallingwater,” a later masterpiece that epitomizes his mature style. This connection highlights the Laura Gale House’s role in the evolution of Wright’s architectural thinking, particularly in its dramatic cantilevered elements. Furthermore, following the publication of Wright’s Wasmuth portfolio in 1910, which included the Gale House, the design made a lasting impression on European modernists, especially those associated with the De Stijl movement in the Netherlands. These architects drew inspiration from Wright’s innovative use of geometric forms and open interiors, which influenced the development of early modern architecture in Europe.

Today, the Laura Gale House remains a cherished landmark, having been meticulously restored by architect Howard Rosenwinkel in 1962 and currently owned by Andrea Kayne and Andrew C. Mead.

The architectural design of the Gale House is modest yet impactful, with its innovative use of space and structure. The entrance, subtly hidden behind a tall pier, opens into a hall dominated by a massive Roman brick fireplace, which artfully separates the hall from the living room. Built-in shelving and slightly elevated dining room floors, along with dramatically cantilevered balconies, are distinctive features that showcase Wright's skill in integrating interior spaces with external forms. The house's second story, which includes four bedrooms and a maid’s room, is enhanced by a cantilevered balcony that joins the north-facing bedrooms, offering a unique architectural element that presages some of Wright's later, more famous works.

The design significance of the Laura Gale House extends beyond its physical boundaries. Wright himself regarded this residence as the “progenitor of Fallingwater,” a later masterpiece that epitomizes his mature style. This connection highlights the Laura Gale House’s role in the evolution of Wright’s architectural thinking, particularly in its dramatic cantilevered elements. Furthermore, following the publication of Wright’s Wasmuth portfolio in 1910, which included the Gale House, the design made a lasting impression on European modernists, especially those associated with the De Stijl movement in the Netherlands. These architects drew inspiration from Wright’s innovative use of geometric forms and open interiors, which influenced the development of early modern architecture in Europe.

Today, the Laura Gale House remains a cherished landmark, having been meticulously restored by architect Howard Rosenwinkel in 1962 and currently owned by Andrea Kayne and Andrew C. Mead.

10) Peter A. Beachy House

The Peter A. Beachy House showcases a dramatic transformation under the architectural guidance of Frank Lloyd Wright in 1906. Commissioned by Emma Beachy, daughter of Peter Fahrney—a successful doctor and real estate investor in Chicago—the project involved a comprehensive renovation of an existing Gothic cottage intended for her children and her second husband, Peter A. Beachy. Wright's intervention was so extensive that little of the original structure was left untouched, with the redesign essentially resting on the existing foundation.

Wright’s design positioned the house on the northern corner of a large lot, a strategic choice that maximizes exposure to natural light, enhancing both the aesthetics and energy efficiency of the home. Architecturally, the house features gabled roofs and presents a striking facade with red brick on the first story and stucco accented with dark wood trim on the upper level. This combination of materials and colors provides a rich texture and depth to the exterior, setting it apart from Wright’s more typical Prairie-style homes, which often use a more uniform material and color palette.

In contrast to the abstract and minimalist art glass typically seen in many of Wright’s designs from this period, the Beachy House features casement windows with heavy wood mullions that add a robust and traditional element to the house’s overall modernist aesthetic. These windows not only contribute to the structural expression of the building but also reflect a unique blend of the contemporary and the traditional, a hallmark of Wright's versatility and responsiveness to client preferences.

Wright’s design positioned the house on the northern corner of a large lot, a strategic choice that maximizes exposure to natural light, enhancing both the aesthetics and energy efficiency of the home. Architecturally, the house features gabled roofs and presents a striking facade with red brick on the first story and stucco accented with dark wood trim on the upper level. This combination of materials and colors provides a rich texture and depth to the exterior, setting it apart from Wright’s more typical Prairie-style homes, which often use a more uniform material and color palette.

In contrast to the abstract and minimalist art glass typically seen in many of Wright’s designs from this period, the Beachy House features casement windows with heavy wood mullions that add a robust and traditional element to the house’s overall modernist aesthetic. These windows not only contribute to the structural expression of the building but also reflect a unique blend of the contemporary and the traditional, a hallmark of Wright's versatility and responsiveness to client preferences.

11) Frank W. Thomas House

The Frank W. Thomas House marks a significant milestone in Frank Lloyd Wright's architectural development, being the first of his mature Prairie-style residences. Completed in 1901, the house epitomizes Wright's philosophy of creating structures that embody organic unity, as he poetically described the Thomas house as flaring outward and "opening like a flower to the sky." This analogy captures Wright's intention to design buildings that not only inhabit the landscape but also interact with it, reflecting his deep appreciation for nature's inherent beauty and complexity.

The house's layout is characteristically L-shaped, a common feature in many Prairie homes, which allows for a natural division of public and private spaces. Wright's ingenious use of design elements such as ribbon windows and dark string courses visually unites the different parts of the house, emphasizing the horizontal planes that are a signature of his Prairie style. These elements also help to integrate the structure with the flat, expansive Midwestern landscape, further underscoring the organic connection Wright sought to achieve between his architectural designs and their natural surroundings.

Innovatively, Wright designed the Thomas House with an elevated main living area, raising it above what would traditionally be considered the ground level. This elevation served multiple purposes: it enhanced privacy, provided a better view of the surrounding landscape, and allowed natural light to permeate the interior more effectively. The main entrance of the house is strategically indirect, creating a sense of discovery and anticipation. Visitors are guided through a series of architectural gestures—a walled walk, a dramatic archway, and a sequence of stairways leading to an expansive terrace and the main entrance. This elaborate entry sequence is not just functional but also theatrical, enhancing the experiential quality of arriving at and entering the home.

The house's layout is characteristically L-shaped, a common feature in many Prairie homes, which allows for a natural division of public and private spaces. Wright's ingenious use of design elements such as ribbon windows and dark string courses visually unites the different parts of the house, emphasizing the horizontal planes that are a signature of his Prairie style. These elements also help to integrate the structure with the flat, expansive Midwestern landscape, further underscoring the organic connection Wright sought to achieve between his architectural designs and their natural surroundings.

Innovatively, Wright designed the Thomas House with an elevated main living area, raising it above what would traditionally be considered the ground level. This elevation served multiple purposes: it enhanced privacy, provided a better view of the surrounding landscape, and allowed natural light to permeate the interior more effectively. The main entrance of the house is strategically indirect, creating a sense of discovery and anticipation. Visitors are guided through a series of architectural gestures—a walled walk, a dramatic archway, and a sequence of stairways leading to an expansive terrace and the main entrance. This elaborate entry sequence is not just functional but also theatrical, enhancing the experiential quality of arriving at and entering the home.

12) Unity Temple

Commissioned in 1905 after the original Oak Park Unity Church was destroyed by fire, Frank Lloyd Wright's Unity Temple stands as a seminal work in American architecture and a crown jewel among Wright’s numerous designs during his Chicago years. The commission for Unity Temple not only provided Wright an opportunity to work closely with a community he was intimately connected with—given his family’s Unitarian background and his own marriage in his uncle’s Unitarian parish—but also to embody the Unitarian virtues of unity, truth, beauty, simplicity, freedom, and reason in his design.

Wright's architectural response was revolutionary, eschewing traditional ecclesiastic designs in favor of a form that was entirely new. He chose reinforced concrete as the primary material, citing budget constraints with the church’s modest fund of $45,000. However, this material choice also allowed Wright to explore the plasticity and versatility of concrete, employing it in innovative ways that would define the building’s unique aesthetic. The structure’s exterior is characterized by a monolithic cubic form, topped with a flat roof and marked by a series of high clerestory windows set back behind decorative piers. These features give Unity Temple its fortress-like appearance, with an almost hidden entryway that leads from a modest doorway into a transformative interior space.

Inside, Unity Temple reveals its true splendor. The sanctuary, which is accessed through a complex entry sequence contrasting with the straightforward entry into the adjoining Unity House, is both majestic and intimate. The space is defined by its elevated coffered ceiling supported by a continuous band of Wright’s signature art glass clerestory windows, allowing soft, natural light to permeate the room and highlight its geometric proportions. The absence of traditional religious iconography and the emphasis on geometric harmony and warm colors emphasize the Unitarian values of inclusivity and intellectual spirituality.

Dedicated in September 1909 and later renamed Unity Temple to reflect its unique architectural and spiritual identity, the building surpassed its initial budget, ultimately costing nearly double the original estimate due to unforeseen construction challenges. Despite these financial overruns, Unity Temple remains one of Wright’s most celebrated works. In recognition of its profound impact on the development of modern architecture, Unity Temple was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019.

Wright's architectural response was revolutionary, eschewing traditional ecclesiastic designs in favor of a form that was entirely new. He chose reinforced concrete as the primary material, citing budget constraints with the church’s modest fund of $45,000. However, this material choice also allowed Wright to explore the plasticity and versatility of concrete, employing it in innovative ways that would define the building’s unique aesthetic. The structure’s exterior is characterized by a monolithic cubic form, topped with a flat roof and marked by a series of high clerestory windows set back behind decorative piers. These features give Unity Temple its fortress-like appearance, with an almost hidden entryway that leads from a modest doorway into a transformative interior space.

Inside, Unity Temple reveals its true splendor. The sanctuary, which is accessed through a complex entry sequence contrasting with the straightforward entry into the adjoining Unity House, is both majestic and intimate. The space is defined by its elevated coffered ceiling supported by a continuous band of Wright’s signature art glass clerestory windows, allowing soft, natural light to permeate the room and highlight its geometric proportions. The absence of traditional religious iconography and the emphasis on geometric harmony and warm colors emphasize the Unitarian values of inclusivity and intellectual spirituality.

Dedicated in September 1909 and later renamed Unity Temple to reflect its unique architectural and spiritual identity, the building surpassed its initial budget, ultimately costing nearly double the original estimate due to unforeseen construction challenges. Despite these financial overruns, Unity Temple remains one of Wright’s most celebrated works. In recognition of its profound impact on the development of modern architecture, Unity Temple was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019.

13) Oscar Balch House

The Oscar Balch House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1911, is an exemplary piece of Wright's architectural prowess during his prolific years in Oak Park. Oscar B. Balch, a successful partner in the local decorating firm of W. and S. E. Pebbles, had previously collaborated with Wright in 1907 to remodel his company's storefront, which likely influenced his decision to commission Wright for the design of his family home.

Wright’s design for the Balch House cleverly conceals its entrance, creating a private, introspective environment that contrasts sharply with the openness inside. The exterior features sturdy walls around the terrace and the southern boundary of the property, forming a robust barrier that might seem imposing if not for Wright's strategic use of casement windows placed just below the roof's soffits. These windows, with their clear panes and wood mullions, not only bring in ample natural light but also soften the building's mass with their crisp, angular placement, enhancing the geometric aesthetics of the structure.

Internally, the Balch House reveals Wright’s genius in creating fluid, interconnected living spaces that maintain a sense of distinct function. The central feature of the house is a large Roman brick fireplace, flanked by slatted screens, which anchors the living space both physically and visually. The ground floor comprises the library, living room, and dining room, which are merged into a continuous open plan yet are subtly delineated by bands of wood that traverse the walls and ceilings. These wooden bands form sharp, geometric patterns that not only unify the different areas but also enhance the architectural rhythm of the space.

The Oscar Balch House stands today as a significant illustration of Wright’s middle career, where his designs began to fully articulate the principles of what would be known later as the Prairie School. This architectural style is renowned for its emphasis on horizontal lines, integration with the landscape, and fluid interior spaces.

Wright’s design for the Balch House cleverly conceals its entrance, creating a private, introspective environment that contrasts sharply with the openness inside. The exterior features sturdy walls around the terrace and the southern boundary of the property, forming a robust barrier that might seem imposing if not for Wright's strategic use of casement windows placed just below the roof's soffits. These windows, with their clear panes and wood mullions, not only bring in ample natural light but also soften the building's mass with their crisp, angular placement, enhancing the geometric aesthetics of the structure.

Internally, the Balch House reveals Wright’s genius in creating fluid, interconnected living spaces that maintain a sense of distinct function. The central feature of the house is a large Roman brick fireplace, flanked by slatted screens, which anchors the living space both physically and visually. The ground floor comprises the library, living room, and dining room, which are merged into a continuous open plan yet are subtly delineated by bands of wood that traverse the walls and ceilings. These wooden bands form sharp, geometric patterns that not only unify the different areas but also enhance the architectural rhythm of the space.

The Oscar Balch House stands today as a significant illustration of Wright’s middle career, where his designs began to fully articulate the principles of what would be known later as the Prairie School. This architectural style is renowned for its emphasis on horizontal lines, integration with the landscape, and fluid interior spaces.

14) Harry S. Adams House

The Harry S. Adams House is the last of the homes Frank Lloyd Wright designed in this suburban Chicago area. Completed in 1913, this residence encapsulates the fully mature Prairie Style that Wright pioneered and perfected during his Oak Park period. The house's architectural features epitomize the distinct aesthetic principles of the Prairie Style, emphasizing horizontal lines, low proportions, and integration with the landscape, which all contribute to its distinctive appearance.

Prominent among its features is the very low hipped roof, which appears almost flat, enhancing the elongated, ground-hugging profile of the house. This is complemented by a broad central chimney that anchors the structure both visually and functionally. The house sits on a concrete stylobate, a feature that elevates it slightly, giving prominence to its horizontal emphasis while still maintaining a seamless connection with its surroundings. This foundation supports the lengthy, flat silhouette of the building, a hallmark of Wright’s designs during this period.

In a unique architectural choice for Wright’s residential designs, the Harry Adams House incorporates art glass windows exclusively on the top floor, adding a decorative yet functional element that allows light to permeate the interior while maintaining privacy and aesthetic continuity. Another distinctive feature of this house is its carport, a rarity among the Oak Park residences designed by Wright. The inclusion of a carport instead of a traditional garage reflects a forward-thinking approach to automotive culture, which was burgeoning at the time.

The Harry S. Adams House not only represents the culmination of Wright's work in Oak Park but also illustrates the architect's commitment to refining and advancing his vision for an American residential architecture. As a pristine example of the Prairie Style, this home serves as a fitting capstone to Wright’s prolific period in Oak Park, showcasing his mastery in crafting spaces that are both aesthetically compelling and intimately connected to their settings.

Prominent among its features is the very low hipped roof, which appears almost flat, enhancing the elongated, ground-hugging profile of the house. This is complemented by a broad central chimney that anchors the structure both visually and functionally. The house sits on a concrete stylobate, a feature that elevates it slightly, giving prominence to its horizontal emphasis while still maintaining a seamless connection with its surroundings. This foundation supports the lengthy, flat silhouette of the building, a hallmark of Wright’s designs during this period.

In a unique architectural choice for Wright’s residential designs, the Harry Adams House incorporates art glass windows exclusively on the top floor, adding a decorative yet functional element that allows light to permeate the interior while maintaining privacy and aesthetic continuity. Another distinctive feature of this house is its carport, a rarity among the Oak Park residences designed by Wright. The inclusion of a carport instead of a traditional garage reflects a forward-thinking approach to automotive culture, which was burgeoning at the time.

The Harry S. Adams House not only represents the culmination of Wright's work in Oak Park but also illustrates the architect's commitment to refining and advancing his vision for an American residential architecture. As a pristine example of the Prairie Style, this home serves as a fitting capstone to Wright’s prolific period in Oak Park, showcasing his mastery in crafting spaces that are both aesthetically compelling and intimately connected to their settings.

Walking Tours in Chicago, Illinois

Create Your Own Walk in Chicago

Creating your own self-guided walk in Chicago is easy and fun. Choose the city attractions that you want to see and a walk route map will be created just for you. You can even set your hotel as the start point of the walk.

Millennium and Grant Parks Walking Tour

The city of Chicago is renowned for its outdoor green spaces. One such “forever free and open” space, is called Grant Park and was established in 1844. In fact, upon foundation, it was called Lake Park, but was renamed in 1901 after the American Civil War General and United States President, Ulysses S. Grant.

Popularly referred to as “Chicago's front lawn,” this lakefront park is... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.7 Km or 1.7 Miles

Popularly referred to as “Chicago's front lawn,” this lakefront park is... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.7 Km or 1.7 Miles

Chicago Introduction Walking Tour

Chicago, perched on the shores of Lake Michigan in Illinois, is a city steeped in history and urban vibrancy. Known by numerous nicknames such as the Windy City and the City of Big Shoulders, it boasts a skyline marked by towering structures. The area of today's Chicago, initially inhabited by Native American tribes, saw its first European-settled reference as "Chicagou" in 1679, a... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.9 Km or 2.4 Miles

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 3.9 Km or 2.4 Miles

The Magnificent Mile Walking Tour

The stretch of Michigan Avenue from the Chicago River to Lake Shore Drive, otherwise known as the Magnificent Mile, is regarded as one of the world’s great avenues – or Chicago’s version of Fifth Avenue. Take this self-guided walk to explore its whole stretch and surrounding area, featuring a wide selection of amazing stores/malls, world-known museums, restaurants and spectacular... view more

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 4.0 Km or 2.5 Miles

Tour Duration: 3 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 4.0 Km or 2.5 Miles

University of Chicago Walking Tour

Founded in 1890, the University of Chicago is among the world’s most prestigious educational institutions. As of 2020, the University’s students, faculty and staff have included 100 Nobel laureates, giving it the fourth-most affiliated Nobel laureates of any university.

Set in the heart of Chicago’s famous eclectic neighborhood, Hyde Park, the campus is worth a visit as it offers a... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.5 Km or 1.6 Miles

Set in the heart of Chicago’s famous eclectic neighborhood, Hyde Park, the campus is worth a visit as it offers a... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.5 Km or 1.6 Miles

Chicago Old Town Walking Tour

Settled in 1850 by German immigrants, Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood is a popular destination for locals and visitors who cater to the entertainment venues, restaurants, pubs, coffee shops and boutiques – all of which have turned an area once referred to as the “Cabbage Patch” into an attraction that rivals Navy Pier, Wrigley Field and the Magnificent Mile.

Start your Old Town walking... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.6 Km or 1.6 Miles

Start your Old Town walking... view more

Tour Duration: 2 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 2.6 Km or 1.6 Miles

Chicago Chinatown Walking Tour

Tucked away just south of the Loop, the Chinatown of Chicago was established in 1912 and is considered one of the best examples of American Chinatown. While it may be one of Chicago’s smallest neighborhoods geographically, it is big on character, colors, sights, sounds, and flavors. Here, you’ll find a wide range of unique boutiques, specialty shops, religious sights, authentic Chinese... view more

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.7 Km or 1.1 Miles

Tour Duration: 1 Hour(s)

Travel Distance: 1.7 Km or 1.1 Miles

Useful Travel Guides for Planning Your Trip

Chicago Souvenirs: 15 Distinct Local Products to Bring Home

One of the most fascinating cities in the U.S., if not the whole world, Chicago has no shortage of things closely associated with it, often due to their direct origin (blues, gangstership, etc.), so one might literally be spoiled for choice as to what to choose as a "piece" of Chicago to...

The Most Popular Cities

/ view all